The Portfolios

The most sensational of Ege’s activities as a book-tearer, and that which is most often referred to, involves the manuscript and printed leaf sets which Ege assembled in the 1930s and ’40s for commercial sale:

Original Leaves from Famous Books, Eight Centuries, 1240 A.D. – 1923 A. D.

Original Leaves from Famous Books, Nine Centuries, 1122 A.D. – 1923 A. D.

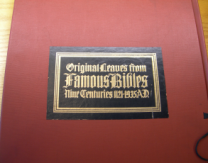

Original Leaves from Famous Bibles, Nine Centuries, 1121 – 1935 A. D.

Fifteen Original Oriental Manuscript Leaves of Six Centuries: Twelve of the Middle East, Two of Russia, and One of Tibet.

A Group of Eleven Original Leaves Showing the Evolution of Humanistic Book Hands and Roman Types from Jenson to Rogers.

Original Leaves. "Incunabula." XVth Century Printed Books.

Fifty Original Leaves from Medieval Manuscripts. Western Europe: XII – XVI Century.

A quick online catalog search will provide additional information on these specimen sets (though not much), and the challenges to bibliography and provenance posed by them quickly become apparent. For example, that they are cataloged without publication dates (to what extent, one might ask, are they publications?), and in some cases they have been entered without Ege’s name as author (to what extent is he their author?). The number of included specimens varies widely among the kinds of sets, from Roman Types’ eleven to Famous Bibles’ 60, but there is some reason to suspect that sets may have been expanded in scope even as they were being disseminated. Never is full information revealing the scope of their presence in the indexed libraries available: Famous Books, Nine Centuries, for example, exists in a numbered series of 110, but other sets seem to exist in vastly limited numbers. Finally, there are storage-related questions which may help explain why relatively few of the sets seem to be catalogued: when an institution is given a choice, should it store and manage these specimen sets in a library, or in a gallery or museum? They are textual objects, of course, but their exhibition quality confers upon them powerful claims to broad usefulness that might be made by a variety of venues; they contain only individual pages from manuscript and printed books, and few (if any) sets contain more than one page from any single bound source.

Many other specimen sets—whether they consist of a handful of items sent out as commemorative tributes, or as massive productions of 200 or more boxed sets—were produced and sold during the 20th century, but most of these were made in collaboration or cooperation with a business (a publisher, a rare book dealer, and so on) or an organization. Konrad Haebler, for example, issued 100 portfolios of 110 leaves each of Italian Incunabula in 1927, under the auspices of Weiss and Co. of Munich; Claus Nissen compiled Herbals of Five Centuries: 50 Original Leaves from German, French, Dutch, English, Italian, and Swiss Herbals, with an Introduction and Bibliography in Zurich in 1958 in an edition of 100 sets, with the assistance of three antiquarian booksellers who owned fragmentary printed herbals and who selected the specimen leaves with Nissen’s input.

In America, the Society of Foliophiles issued several leaf books in the late 1920s (e.g., Specimens of Oriental Mss. and Printing, 125 sets of 46 specimens each; Specimens of Woodcuts and Engravings, 120 sets of 16 specimens; Printed Pages from European Literature, 200 sets of 20 specimens), and then in the 1960s a four-part set of leaves collectively entitled Pages from the Past—a seemingly innocuous title belying the actual portfolios’ vexingly inconsistent contents (the various parts contain between 18 and 60 sets of between 24 and 145 leaves each). The Book Club of California, which Lilly Library curator Joel Silver calls “one of the most prolific publishers of individual leaf books,” moreover, adds to our uncertainty about the scope of these fragment collections by disseminating its leaf books only among a limited, private membership. As Silver goes on to say, “There is, as yet, no accurate tally of all the leaf books that have been produced, but the total probably exceeds 250, especially if one includes portfolios of leaves, such as those produced by Ege and Haebler, and the many private press bibliographies that include original leaves taken from some of the publications described.” [17] Since all 20th-century leaf book sets seem, on the whole, to resist stable content description, and since some of them have suffered gentle attrition of their contents by innocent pilfering for the sake of library, office, or gallery decoration, the challenge of provenance multiplies itself to a truly astonishing degree.

Nevertheless, the profit and delight provided by these study sets is delicious: they absolutely provide the kind of hands-on material study of medieval technique for which Ege intended them. At a small college like Denison University, for example, which is devoted to undergraduate liberal arts education and which is not otherwise well-stocked with pre-modern materials, both introductory survey courses and more advanced medieval and early modern seminars benefit immeasurably from the discussion that such fragmentary resources inspire. There is a magnetic, mnemonic quality to encountering text objects 500 or 1,000 years old, even if a student’s encounter with them is relatively brief and superficial. In more advanced and extended teaching situations (at Denison, this usually takes the form of independent projects in paleography in anticipation of graduate school in History, English, or Library and Information Science), proximity to this kind of resource is absolutely essential to bring to life the observations of art historians and textual scholars like Pächt, Greetham, and others.

Click "Next" below to continue, or "Previous" to go back.

______________________________

[17] Joel Silver, “Beyond the Basics: Leaf Books” (Fine Books and Collections, 2005) http://www.finebooksmagazine.com/issue/0205/leaf_books.phtml (accessed 15 October 2006; click here to go there directly). See also the home of The Book Club of California. Digital technology, of course, helps improve understanding about these leaf books, as the project set into motion by the 2005 Saskatoon conference demonstrates. Online exhibits of leaf books include the Foliophile virtual exhibit by the University of South Carolina; the electronic counterpart of the Newberry Library/Caxton Club exhibit from the summer of 2005; and the Caxton Club's own online exhibit on leaf books. The "Links & Bibliography" tab to the left connects to more sites with Ege-specific content.