Exhibitions and Lectures

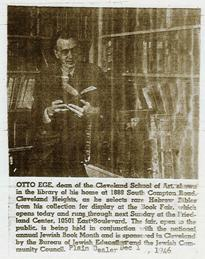

Announcement of an exhibit of Ege's Hebrew books for the Cleveland Book Fair. (The Plain Dealer, December 1946.)

In the 1930s Ege began holding exhibits and gatherings in his home to display his personal acquisitions, and the newspaper announcements of these events show a manifest pride in his ability to gather and share unusual book art. He gave dozens of public lectures, and loaned materials to libraries and museums frequently as well: one of his accomplishments was the nearly-single-handed sponsoring, in 1940, of the Cleveland Public Library’s 500th anniversary celebration of the invention of printing, called by admirers “the finest assembled between New York and the Pacific Coast.” Events like these gradually broadened in scope through World War II, until, in the later 1940s, records exist of Ege loaning items to local book and art shows several times a year. [7]

When he died in Cleveland in 1951 at the age of 63, his estate was valued at $58,500—the majority of it the contemporary valuation of his book and leaf collection. His 1950 Pontiac, otherwise “the most tangible item among the dean’s personal possessions,” was valued at $1,600. Listed among his property at the time, and in addition to the intact or semi-intact bound volumes of various kinds, were no fewer than 3,400 detached medieval manuscript leaves he had collected over the previous quarter-century. [8] These materials provide a tantalizing and rich opportunity for studying the modern provenance of medieval textual artifacts, and are now the focus of international interest. A small selection of his holdings is described in the De Ricci Census in 1935, but today, fifty years after his death, a detailed public inventory of Ege’s collection has yet to be undertaken. [9]

An Ege lecture in 1934.

The tremendous inspirational value of hands-on manuscript and early

book study is widely recognized, and though Ege’s social and

educational efforts are now sealed in the 20th-century past his

published work exhibits consistent advocacy of that value. His many

publications readily divide themselves into three categories: writings

on bibliography intended to broaden the historical awareness of a

popular audience; essays which advocate art education for the American

public, especially at the grade school and high school levels; and,

finally, commercial specimen sets of medieval, early modern, and modern

book leaves constructed in order to facilitate those first two goals.

Ege authored several essays in public venues in the 1920s and ’30s, both on general topics (“Manuscripts of the Middle Ages”) and more specific ones (“The Most Beautiful Book in the World,” on the Book of Kells), in which he introduced book manufacture and decoration in lay terms. It was also in the 1920s that Ege wrote his two book-length introductions to writing systems, The Story of the Alphabet and Pre-Alphabet Days. His desire to teach art, and to teach teachers of art, displays itself in essays such as “The Main Highway of Art Education” and “Teaching Appreciation through Expression,” both of which appeared in regional arts education journals. [10] In neither of these areas of publication, however, can Ege be considered a scholarly pioneer or a leading voice: he was a passionate advocate, and certainly his writings display a valid trust in the inspirational power of experiential learning. His descriptions and evaluations of historical book forms, however, tethered as they are to the general audiences for which he consistently wrote, are of relatively little note to paleographers and book historians today except as they inform his other activities.

Click "Next" below to continue, or "Previous" to go back.

______________________________

[7] Dean Otto F. Ege, VI.

[8] “Dean’s $58,000 Estate Consists of Rare Books,” Cleveland Press, November 2, 1951.

[9] Seymour De Ricci, ed., Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada (New York: American Council of Learned Societies, 1935-40), vol. 2, 1937-48. This listing is not exhaustive, but shows that by the 1930s Ege’s collection ran the gamut of physical condition from excised initials and individual leaves, to bifolia, gatherings, and fragmentary codices, to intact bindings. Other parts of the Census directly relevant to the study of Ege include the descriptions of the libraries of Mrs. Milton E. Gertz (vol. I, 12-16), Ernst Detterer (I, 601-07), and Alfred Mewett (II, 1953-57), as well as the Grosvenor Library in Buffalo (II, 1209-12) and the Stevens Gallery in Toledo (II, 1972-77). In C. U. Faye and W. H. Bond’s Supplement to the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1962), see for example the entries on the libraries of Dorothy Schullian (429-30) and Hollins College (now Hollins University) (524-5).

[10] A comprehensive list of Ege’s written works is contained in a typescript Bibliography of the Publications of Otto F. Ege (1888-1951), Late Dean of the Cleveland Institute of Art. Compiled and Edited by the University Libraries and the School of Library Science, Western Reserve University (Cleveland: Western Reserve University, 1951), a copy of which is contained in the Microfilm Memorial. The works mentioned by name in this essay are: “The Main Highway of Art Education,” Eastern Arts Association Bulletin 26 (January 1936): 8-12; “Manuscripts of the Middle Ages,” American Magazine of Art 23 (November 1931): 375-80; “The Most Beautiful Book in the World,” School Arts 21 (April, 1922): 446-50; Pre-Alphabet Days (Baltimore: Munder, 1923); The Story of the Alphabet (Baltimore: Munder, 1921); and “Teaching Appreciation through Expression,” Western Arts Association Bulletin (1924): 137-42.